‘An opportunity to dream’ for one young woman with sickle cell disease

Edmonton’s Revée Agyepong was cured of sickle cell disease with stem cells from her sister

Revée Agyepong has always been close to her sister Stephanie, but their bond grew even tighter when she learned that Stephanie could become her stem cell donor.

“We actually found out the news on her birthday, which was just crazy,” Revée said. “We were going out for her birthday dinner but we ended up with two things to celebrate that day.”

Revée, 28, soon became one of the first adults in Canada to receive a stem cell transplant to cure sickle cell disease. The disease is caused by a genetic mutation most often found in people of African descent. It causes the normally round red blood cells to be distorted into a sickle, or crescent, shape which can get stuck in blood vessels.

In Revée’s case the illness produced crippling pain and infections that required hospitalization. This was despite access to top-of-the-line medication and regular therapy that exchanged her own red blood cells with healthy ones from donors.

“Life before the transplant was really tough for me,” Revée said. “It was a really scary place to be, knowing that the strongest medications and best physicians couldn’t find a way to keep me out of the hospital.”

‘It was really fun to discover my new normal’

The transplant in November 2017 cured her illness by replacing her own blood-forming stem cells with new ones from her healthy older sister — who had just a one-in-four chance of being a match.

Today Revée is thriving. She’s avoided the most serious immune complications that can follow the procedure. She also works full-time as a nurse. And, before the COVID-19 pandemic, she was able to go swimming, an activity she used to avoid because the cold water would send her into a health crisis caused by sickling of her red blood cells.

“About a year after transplant I took swimming lessons to learn how to swim and I’m actually not half bad,” she said. “It was really fun to discover what my new normal was and what my life really could be like.

“It gave me an opportunity to kind of dream again, and realize that there is no restriction now.”

Revée Agyepong, right, was cured of sickle cell disease by stem cell transplant. Her sister Stephanie Amoah, left, donated the cells. They’re contained in the bag Revée is holding in this picture taken the day of the transplant.

The promise of stem cells

Revée’s story is a testament to the amazing promise of stem cell transplant. The procedure has been used for decades to cure blood cancers but advances in transplant medicine are now spreading hope to some patients with other blood disorders.

Prior to Revée’s transplant at the Tom Baker Cancer Centre in Calgary, specialists in that city had already cured sickle cell disease in several children using stem cells from matched siblings.

However, treatment for the disease with cells from unrelated donors is still experimental, according to Dr. David Allan, a hematologist and medical director for Canadian Blood Services Stem Cell Registry and Cord Blood Bank. Transplants using unrelated donors are more likely to cause complications that a sickle cell patient might not tolerate well, or even survive.

That reliance on sibling donors is discouraging for most sickle cell patients who don’t have a match in their own family but Dr. Allan is hopeful.

“This is definitely cutting edge, an evolving practice, and I think if we forecast ahead, it’s likely that we can overcome this,” he said.

Success could hinge on both better transplant regimens and bigger registries of stem cell donors. A young person of African origin who joins the stem cell registry today could become a donor for a sickle cell patient in a clinical trial. That person could also be called upon to donate years from now, should the treatment become more established.

“In order to move this field forward, we need more people on the registry who could be donors for people with sickle cell disease,” said Dr. Allan.

Families of newborn babies could also help. Umbilical cord blood is rich in lifesaving stem cells and is easy and free to donate. Because the cells are immature, it means that perfectly matching a patient’s immune system with that of the donor is not always needed, making it easier to find an appropriate option for patients.

Cord blood isn’t yet an established treatment for sickle cell disease, but Dr. Allan believes this may change.

“It motivates me to keep growing the public cord blood bank,” he said. “Once they figure out how to do the cord blood transplants better and more safely, we’re going to be ready.”

Canadian Blood Services’ cord blood program has temporarily stopped collecting and processing cord blood units because of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, healthy Canadians between 17 and 35 years of age can still join Canadian Blood Services Stem Cell Registry online and get a swab kit delivered in the mail.

Dr. David Allan is a hematologist and medical director for Canadian Blood Services Stem Cell Registry and the national public Canadian Blood Services Cord Blood Bank.

Demand for diversity

Patients who need donor stem cells for any illness are most likely to find a match within their own ethnic group.

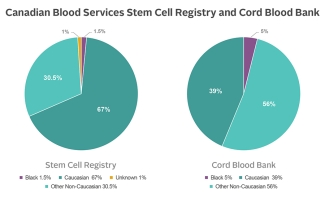

However, the Black population — which includes the vast majority of those suffering from sickle cell disease — is poorly represented in stem cell registries worldwide, including Canada’s. Only 1.5 per cent of the adults in Canada’s stem cell registry are Black.

The numbers in Canadian Blood Services’ Cord Blood Bank are more encouraging but matching Black patients remains a challenge. By accident of evolutionary history, the Black population has great genetic diversity, including in the genes relevant to stem cell matching.

Dr. Allan explains the implications by analogy. Imagine a card game where players with 52-card decks deal themselves hands of eight cards apiece. Then one player surveys the rest, looking for another with a matching hand. It sounds challenging, but not impossible with a large pool of players.

That’s the experience of a Caucasian patient seeking a stem cell match. For Black patients it’s altogether different.

“Instead of having a deck with 52 cards, you’ve got a card deck with 5,000 cards. And now play the game,” explained Dr. Allan. “Now you can see you need to have many, many more (players) in order to find a match.”

Boosting diversity in stem cell registries and cord blood banks can help change the game for Black patients, as could the growth of new registries in African countries.

Without that diversity, physicians in Canada and beyond are challenged to provide the best treatment, even for patients with conditions where stem cell transplant is a well-established therapy.

“Sometimes patients of non-Caucasian ethnicities are being pushed to use imperfect or mismatched donors, which increases the complication rates,” said Dr. Allan.

Revée Agyepong received a stem cell transplant in November 2017 to cure sickle cell disease.

A story of hope

Revée Agyepong is well aware of her good fortune as an early recipient of stem cells to cure sickle cell disease.

“Some people have six siblings, but none of them are matches. Somehow, I was on the very lucky end of things,” she said. “It would be lovely if more research could be put into figuring out ways for people who don’t have sibling matches to get transplants safely.”

Revée now helps by telling others about how she managed to thrive with her disease, and about her recovery.

“They always feel very hopeful and that’s one reason I really love sharing my story,” she said. “Regardless of the disease, sickle cell or something else, the way modern medicine is moving, there is hope for you.”