A kidney donor empowers a storyteller to help others thrive

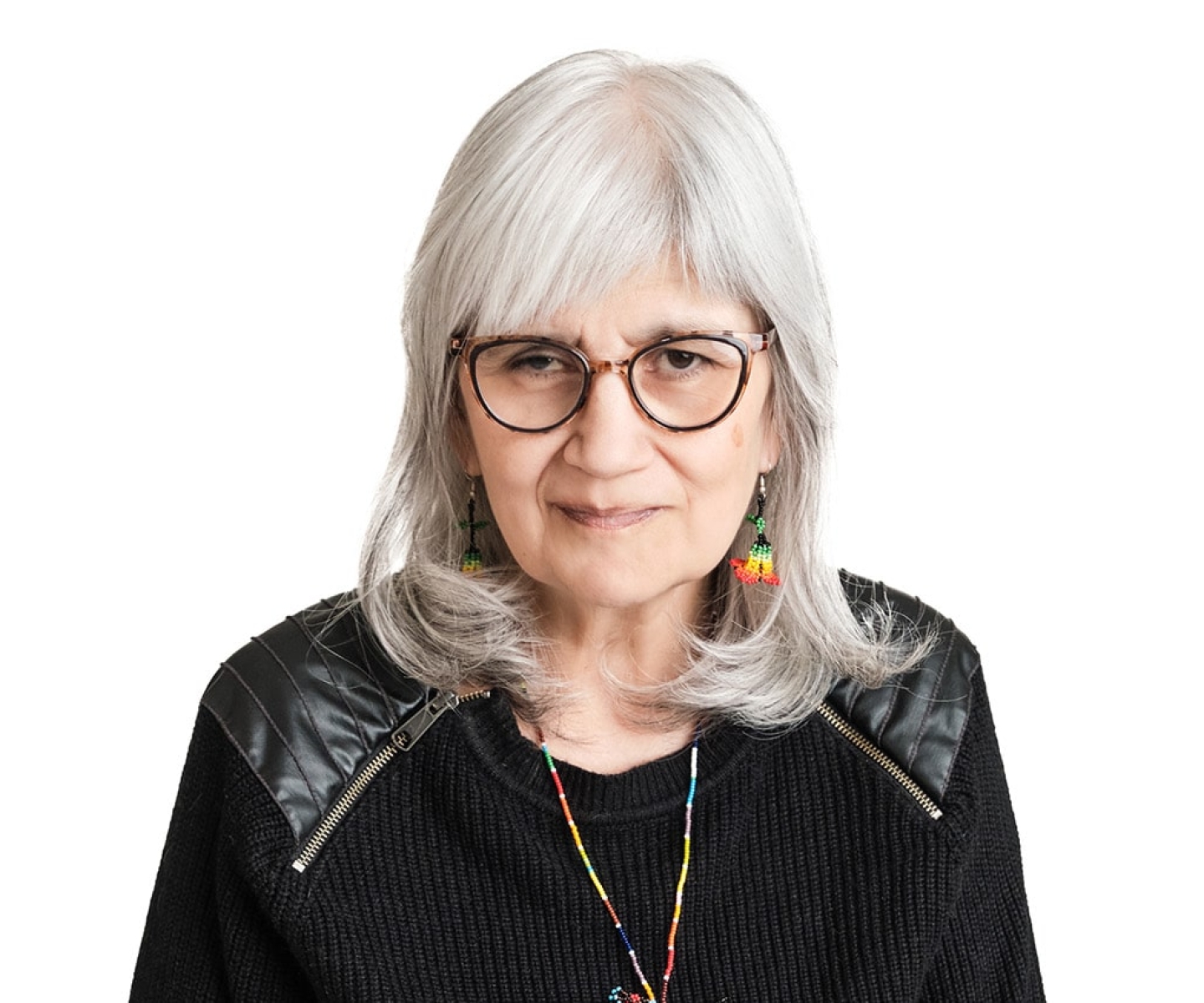

Since her own kidney transplant, Mary Beaucage has worked to improve health systems for other Indigenous patients with kidney disease

A kidney donation in 2015 didn’t just free Mary Beaucage from dialysis. It empowered her to work to improve care for others, especially Indigenous patients — and in doing so, to be a part of strengthening their communities.

“For us to have our health, to have our physical strength even, that helps us do the work to regain culture, language and traditions,” says Mary, 53, who lives in Nipissing First Nation in northern Ontario. “When I was on dialysis, I wanted to go to language classes to study Anishinaabemowin on days when I didn’t have treatment. But I had such brain fog I couldn’t retain anything.

“Learning about plants as medicine, or history, or building a lodge — you can’t do any of that if you’re on dialysis. You just can’t.”

Sharing a journey with kidney disease to help others

Mary helped develop the Transplant Ambassador Program, which connects past kidney donors and recipients with people who are facing a transplant or thinking of donating a kidney. Since her transplant, she has also volunteered extensively with Can-SOLVE CKD. It’s a Canadian patient-oriented kidney research network, where she co-chairs a council that ensures Indigenous knowledge and perspectives are incorporated in all efforts. And she helps lead work by the Canadian Donation and Transplantation Research Program to improve a culture of donation in governments, hospitals and society.

One of the most important things she does is share her own story widely, including with people who have the power to change health systems.

“Storytelling is part of our tradition as Anishinaabe people,” says Mary. “Sharing the things I’ve gone through helps build relationships, whether it’s with other patients, researchers or policymakers.”

Her story certainly illustrates many of the challenges faced by patients with chronic kidney disease, including Indigenous people, who are at higher risk of the illness compared with non-Indigenous people in Canada.

“For us to have our health, to have our physical strength even, that helps us to do the work to regain culture, language and traditions.”

Mary Beaucage, organ recipient, storyteller

Mary’s road to kidney transplant

Mary’s journey began with a frightening episode in June 2013. One evening, feeling very unwell, she headed to a hospital emergency room with her mother, only to be sent home after an exam that was both brief and troubling. Some questions from medical staff seemed rooted in anti-Indigenous racism and stereotypes.

“All they did was check my blood sugar with a glucometer,” recalls Mary, who is diabetic. “No blood work or anything. And then they asked my mom if I usually talk with a slur, if I was on drugs, or did I drink. Or did I go out for long periods and not come back. My mom was saying ‘No, no, none of that.’”

In fact, Mary’s kidneys were failing. The next day, she woke up in such a weak and confused state that she couldn’t even dial 911 on her phone.

Fortunately, when she was late to work, a colleague checked in and was able to call for help. Paramedics brought her back to the hospital. This time, she had X-rays and blood tests before suffering a seizure and falling into a coma.

She awakened four days later connected to a dialysis machine, which was doing work her kidneys could not: removing toxins from her blood. Still, the seriousness of the situation took a while to sink in.

“At first, I thought dialysis was just a temporary measure to get my kidneys kickstarted again, and that I’d be fine after that,” Mary recalls.

Instead, her life changed completely. She had to go on a special diet and spend hours at the hospital three times a week for dialysis. Exhaustion, brain fog and the demands of treatment forced her to quit her job in retail management.

Her only hope was a kidney transplant.

Organ donors make all the difference

At any given time, thousands of people in Canada are waiting for a kidney. The number of organs available from deceased donors falls far short of the need; in fact, hundreds of patients die waiting each year.

The alternative is a living donor. Many healthy adults can safely donate one of their kidneys to a family member, friend, colleague, or even a stranger. And if a prospective donor doesn’t match their intended recipient, the two of them may also choose to participate in the kidney paired donation program. That program allows one willing donor to essentially swap places with another, so that two patients can receive compatible organs from people who remain anonymous to them.

Mary knew little about living donation when she became ill. But the expected eight-year wait for a transplant made her determined to learn everything she could — as well as to educate potential donors in her own network.

Her efforts paid off. Several of her relatives and friends went through the process of getting tested to be a kidney donor. One of them was Janice Pulak, a cousin in Thompson, Man. She was just a year older than Mary and had been her pen pal through childhood.

When Janice matched and agreed to donate, Mary’s wait for transplant shrunk from eight years to two.

“I just felt this real gratitude,” says Mary. “When I share my story or talk about organ donation, I can’t talk about Janice without crying, because what she did was absolutely amazing to me.”

ARE YOU ELIGIBLE TO BE A LIVING KIDNEY DONOR? Find out now

She was also keenly aware of how lucky she was compared to many other patients, including some of her own loved ones.

“We’ve had family members who have gone through dialysis and have passed away while on dialysis,” says Mary. “I think I’m one of the first ones in my family who actually had a transplant.”

A second chance that also helps a family thrive

Last July, Mary and Janice were able to see each other for the first time since the transplant. They, and dozens of family members, gathered for several days for a celebration of their Uncle Peter’s life.

“We always pick up like no time has passed,” Mary says. “I carry part of her with me. It was just very good.”

That gift she carries has made all the difference not just to her, but to so many others. That includes her own family, where she helps keep her son, Tyler, and her 13-year-old grandson, Rylan, connected to their extended family, history and culture.

The summer gathering was an opportunity for Mary to see both of them take part in Indigenous traditions such as the sacred fire and pipe ceremony, which Rylan experienced for the first time. Without a transplant, she likely would have missed that important moment, and the chance to encourage their effort to reclaim tradition.

“They were eager to participate and it was really good seeing that,” Mary says. “It’s a part of reconnecting. We’re all at different parts of this journey of reclaiming our heritage and our practices that were outlawed by governments in Canada for generations.”

Learn more about organ and tissue donation

MORE WAYS DONORS MAKE ALL THE DIFFERENCE

- Plasma donors fuel a sign language teacher’s dreams

- Thanks to a stem cell donor, a father-son bond endures and evolves