After donating stem cells to her father, she’s bringing hope to others

Lauren Sano’s powerful personal story inspires people of diverse backgrounds to join the stem cell registry — because lives depend on it.

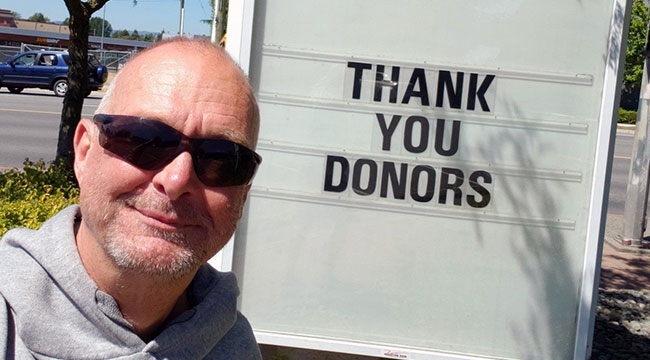

Lauren Sano (left) donated stem cells to her father, the late Mark Sano (right). Lauren donated as a partially-matched donor after no fully-matched donor could be found through Canadian Blood Services Stem Cell Registry.

Anyone, anytime could develop a life-threatening condition that requires a stem cell transplant. But not everyone has the same chance of finding a matching donor.

It’s a lesson Lauren Sano learned in a most painful way after her father, Mark Sano, was diagnosed with a rare blood cancer called mixed phenotype acute leukemia. At the time, she was just 16 years old, the oldest of three siblings.

“No one in my family had been this sick before,” says Lauren, who grew up in Toronto, Ont. “I didn’t really know what to expect.”

Mark, who was a healthy, sports-loving 50-year-old before the diagnosis, was recommended for a stem cell transplant after gruelling rounds of radiation and chemotherapy. Stem cells, specifically blood stem cells, are immature cells that can develop into any cell present in the blood stream. Transplants from healthy donors are used to treat more than 80 diseases and disorders. For many patients, including Mark, a transplant is the only hope of survival.

Mark Sano, seen here at left with his daughter Lauren, required a stem cell transplant for a rare blood cancer.

The search for a stem cell match

A stem cell donor must match the patient in terms of particular proteins found on the surface of white blood cells and other tissues. A patient’s best hope for a match is with a person of similar ancestral background. Mark’s own background was Japanese.

Sadly, no match was available for him in our own stem cell registry, nor in the many international databases to which we have access. Prospective stem cell donors of Japanese ancestry are underrepresented in registries around the world. In fact, donors of northeast Asian heritage, which include those of Japanese and Korean descent, make up only one per cent of our own registry’s total. People of Chinese descent make up seven per cent, while those of European ancestry make up more than two thirds.

With no fully-matched donor available through the registry or within the family, doctors turned to Lauren. She was a partial match for her father, or “haploidentical” — an option which a transplant centre may select when a fully-matched donor is not available.

“I didn’t hesitate at all,” Lauren says. “Especially since the doctor told me there were really no side effects, and the procedure wasn’t painful.”

Donating stem cells: how does it work?

Before donating in March 2019 at Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids), Lauren had injections to stimulate the release of stem cells into her bloodstream. Then the donation itself was similar to the process of donating other blood components such as plasma or platelets, though it took place over several hours. The process, called “peripheral blood stem cell collection,” is the method used for more than two-thirds of stem cell donations; a much smaller number of people are asked to donate bone marrow, which requires general anesthesia.

After the transplant, Lauren received a special necklace from her father when she visited him in the hospital. While delicate, to her it was a symbol of a powerful bond and hope for the future.

“It was a very emotional day,” she remembers.

Lauren’s gift of stem cells allowed Mark to enjoy another year and a half with his family, including tennis matches with his daughter. He died in October 2020 of sepsis, the body’s extreme response to infection, after struggling with post-transplant complications such as difficulty breathing and pneumonia.

Her family will never know for sure, but Lauren will likely always wonder if a more precise stem cell match could have given her dad more years of life and health. And that fuels her commitment to help other patients, including those whose only hope is an unrelated donor.

Immediately following Mark’s death, Lauren began volunteering with Stem Cell Club. This club’s volunteer chapters at post-secondary schools across the country have recruited tens of thousands of prospective stem cell donors. They’re committed to increasing the registry’s ethnic diversity, as well as recruiting males, whose stem cell donations appear to produce better outcomes for patients overall.

Lauren Sano donated stem cells to her father, Mark Sano, after he was diagnosed with a rare form of leukemia. Doctors turned to her as a partial match after no fully-matched donor could be found through the stem cell registry.

Lauren is currently the president of the club’s chapter at Western University, where she is heading into her fourth year of study in kinesiology. Since she joined, she and the other members have delivered virtual presentations to the university’s many ethno-cultural clubs.

“We talked about what stem cells are, what transplants are and why they’re important, and then I would share why it was important to me,” she explains. “When I shared my story, people were able to relate more, as opposed to it being like a science lecture.

“At the end, we’d have a question and answer session, and people would comment that they weren’t aware that the need for diversity in the stem cell registry was such a big issue. They’d ask about how to join, and about whether donation was painful. Just wanting to learn more.”

Working to increase the diversity of the stem cell registry

In early 2022, Lauren also led a special campaign called East Asians Save Lives to coincide with Chinese New Year. Stem Cell Club volunteers created and shared compelling materials online with their networks across the country, to encourage donors of Chinese, Japanese and Korean descent to join the stem cell registry.

The campaign’s YouTube videos, TikToks and other materials remain available for sharing during Asian Heritage Month in May and beyond. In one of those videos, Lauren shared her personal story. She also appeared in a series of posts for Stem Cell Club’s “Why We Swab” library on Instagram and Facebook.

Even teens can register to donate stem cells

More recently, Lauren and four other members of her Stem Cell Club chapter delivered a presentation to high school students in London, Ont. They hope to do more such presentations next year, and encourage other club chapters across Canada to do the same in their communities.

People as young as 17 — Lauren’s own age when she donated stem cells for her father — are eligible to join the stem cell registry. And the sooner a registrant joins, the more years they can be available to be matched to patients in need. While many registrants are never matched to a patient, a very small number may be asked to donate twice (the maximum).

Having joined the stem cell registry herself, Lauren is fully prepared to donate again, for a stranger in Canada or across the world should the need arise. Even through the pandemic, stem cells from Canadian donors are being shipped to patients overseas, while stem cell donations from international donors have also saved lives in Canada.

Lauren’s experience with her father has been life-altering in so many ways. Not only has she felt moved to advocate, but she also aspires to a career in medicine. She’ll spend summer 2022 completing an internship at the Harvard Stem Cell Institute in Boston, Mass.

“I’m also interested in stem cell research, and I hope to work on projects involving therapeutic treatments in the future,” she says.

Currently, fewer than one third of potential donors in Canadian Blood Services Stem Cell Registry are non-Caucasian, and finding matches for patients of Indigenous, Asian, South Asian, Hispanic, mixed-race, and diverse Black backgrounds is difficult. We strongly encourage people aged 17 to 35 who share those backgrounds to join the registry online. Together, we are Canada’s Lifeline.