IVIg, the wonder drug you’ve probably never heard of – yet

Wednesday, February 24, 2016 Lisa Willemse

Wonder drug it may be, but IVIg is a slippery fish. Even after 60 years, little is known about precisely how it works.

An encounter with a scientist

The first thing you notice when you walk into Dr. Don Branch’s office at 67 College Street in Toronto is how small it seems. And colourful, owing to an impressive collection of memorabilia that suggests a full and perhaps eclectic life: show posters, photos of his family and small items such as those one would get from a student or colleague sharing an inside joke. Copious as they are, the richness-of-life souvenirs are nearly crowded out by shelves and stacks of books and what appear to be research papers, some in folders, most not. The stacks disappear into the shadows of Branch’s sparsely lit room.

It’s almost as mysterious and as awe-inspiring as IVIg, or intravenous immunoglobulin, a plasma product used to treat a range of different conditions – and a topic that elicits an immediate and unequivocal amount of passion from Branch, who views it as one of the marvels of modern medicine. I’m here to find out why.

I’ve placed my recording device on a remarkably clear desk. Later, Branch will tell me that Einstein is one of his heroes, but now as I sit down to begin the interview, I briefly ponder Einstein’s quote about the state of one’s surroundings being a reflection of the mind. An empty mind this is not.

But you need not look at Branch’s office to figure this out. The notion is quickly evident with a glimpse at the range and depth of Branch’s research, which spans about 30 years and includes initial work in stem cells before turning his attention to the blood system, transfusion medicine and phagocytosis, the process by which our immune cells identify and devour foreign particles.

His accolades include a key early discovery in HIV back in the 1990s. He still pursues HIV research and speaks with obvious pride of his achievements in that space, but his enthusiasm edges noticeably upward when we turn to the topic of IVIg.

“IVIg has got a huge track record of safety - though there are some significant side effects that include hemolysis and thrombosis events. But, for the most part, it's a miracle drug.” he said.

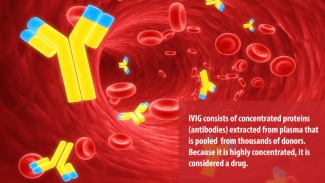

Strong words, to be sure, especially when connected with a therapy that many people have never heard of. First used in 1952 to treat immune deficiency, IVIg is a plasma protein product containing the pooled antibodies of thousands of donors. For patients who receive multiple IVIg treatments per year, it represents a critical boost of immunity to help their body fight infection or forestall the progress of an autoimmune disorder. For others, one dose of IVIg can be an outright cure.

A wonder drug is not without its challenges

Wonder drug it may be, but IVIg is a slippery fish. Even after 60 years, little is known about precisely how it works. Its efficacy varies from person to person, even among those with the same disorder, and can vary from treatment to treatment even in the same patient.

And then there are those rare complications. There are blood clots (thrombosis) to watch for, and, inexplicably, some patients contract IVIg-associated hemolysis, a condition in which the introduced antibodies find a marker on the patient’s red blood cells and attack them, causing the cells to rupture. The easy answer would seem to be that the patient should not receive IVIg therapy, but of course, it’s not that simple.

“If a person has one of these reactions to IVIg, the next time they get IVIg they may not,” explained Branch. “It doesn’t make sense to most people either, why would they have one incident and not a second, even with the same lot? It is a black box in many ways.”

Still, these unknowns are not enough to take IVIg off the list of approved therapies, especially when it is the only viable one for conditions such as common variable immunodeficiency or Kawasaki disease. Nor is the expense of production and the fact that Canadian patients must rely on product being made outside Canada – mostly in the US.

An ounce of prevention…

And it’s precisely these challenges that have Branch looking for answers. One of his current concerns is that black box of hemolysis, which affects about 35 per cent of patients (when including all grades).

“The goal for me is to see if we can put our finger on something that would be easy to test before patients get the IVIg to know who’s going to have a chance of hemolysis and who isn’t.”

Branch went on to explain that the varied responses point to something different within the patient’s immune system that changes, rather than the cause being present in the drug, which undergoes a rigorous standardization process.

Branch’s money – or at least his research – is on a cytokine, a type of small protein that is secreted by cells and can signal a particular action in other cells. In this case, the cytokine in question, named IL-1ra, is part of a family that is central to the body’s immune and inflammation response. His theory is that elevated levels of IL-1ra prior to receiving IVIg may be a signal of higher risk that the patient will experience a hemolytic reaction.

Of course, there may be other cytokines that herald a hemolytic episode in response to IVIg therapy; that is why Branch is investigating 40 different cytokines in a Canadian Blood Services’ funded prospective study of patients receiving IVIg for various conditions.

Another test that is being used by Branch is one that he pioneered and continues to use. “We are using a test called the monocyte monolayer assay, which I pioneered way back when, to look at activation of the patient’s monocytes,” said Branch. Monocytes and macrophages are types of white blood cell – one of the defensive cells that identifies and attacks foreign intruders in the bloodstream, and is chiefly responsible for the unwanted attack on red blood cells in the case of IVIg-associated hemolysis.

“The idea,” said Branch, “is that we can actually measure whether or not the patient’s monocytes are more active than not and thus predict whether a hemolytic response would occur.”

It’s only one thing to look for, however. Another indicator of an adverse reaction to IVIg treatment is the presence of a mutation on the monocytes/macrophages that creates a heightened sensitivity to antibodies present on red blood cells, thereby increasing the likelihood of an immune attack. This mutation can be detected through a DNA test, but it takes longer to obtain the results than the monocyte test.

Branch is also involved in a fourth area of interest, in collaboration with Dr. Elisabeth Maurer, founder of LightIntegra Technologies, which is examining levels of microparticles as a measure of an inflammatory condition existing prior to receiving the IVIg.

Pulling one or more of these indications into standard tests that could be administered to patients in advance of an IVIg treatment would enable medical professionals to avoid an adverse hemolytic reaction and would go a long way in helping us understand the mechanism of IVIg-mediated hemolysis.

The hunt for alternative treatments

While greater understanding will inevitably help reduce risk for patients and costs for the health care system, it does little to address the cost of the therapy in Canada, given that plasma donation is only a fraction of what’s needed.

Currently, plasma donated at many Canadian Blood Services collection sites is sent to the US or Europe for processing, in part due to this lack of volume, but also because no such facility yet exists in Canada. Globally, there is enough IVIg to spare, but it is an expensive treatment option, which is one reason the number of illnesses approved for IVIg therapy is relatively small.

IVIG is licensed by Health Canada for treatment of primary and secondary immune deficiencies, allogeneic bone marrow transplantation, chronic B-cell lymphocytic leukemia, pediatric HIV-infection, Kawasaki disease and idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. There are many “off-label” (not on Health Canada’s licensed list) uses for IVIG, which may account for a sustained demand in Canada.

It’s also why Branch and a number of others are seeking alternatives. Branch is looking to drug discovery that might help prevent an adverse immune response in the blood. But he predicts that a non-plasma IVIg replacement may not be too far away.

“One bit of published work involves making a recombinant protein [essentially a protein obtained from DNA mixed to get a desired product] that they think is the effector molecule, and they showed it works tenfold better in animal models than does IVIg. And not just in immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) but in an arthritis mouse model and autoimmune psoriasis, showing that the recombinant protein worked extremely well in all of these different models.”

Assuming that these studies can progress safely into the clinic, Branch has high hopes for what it will mean for medicine.

“It truly is a wonder drug,” he reiterated. “There’s aspirin. That was the first miracle drug. Then statins – the cholesterol drugs – that’s the second one. And then, it’s IVIg.”

Dr. Donald Branch is a Scientist with Canadian Blood Services’ Centre for Innovation. His lab is located at 67 College Street in Toronto. He is also an Associate Professor at the University of Toronto. Dr. Branch’s research aims to understand the pathogenesis and functioning of cells in various diseases that require blood transfusion products and related biologics. In particular, Dr. Branch studies mononuclear phagocytes to understand and inhibit the phagocytosis function of these cells in autoimmune diseases and, using animal models of autoimmune diseases, the mechanism of amelioration by intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) therapies.

Keywords: IVIg, intravenous immunoglobulin, autoimmune, research, plasma, science

Canadian Blood Services – Driving world-class innovation

Through discovery, development and applied research, Canadian Blood Services drives world-class innovation in blood transfusion, cellular therapy and transplantation—bringing clarity and insight to an increasingly complex healthcare future. Our dedicated research team and extended network of partners engage in exploratory and applied research to create new knowledge, inform and enhance best practices, contribute to the development of new services and technologies, and build capacity through training and collaboration.

About the Author: Lisa Willemse is a communications professional with 18 years’ experience working in the technology, child development and health research fields, and is currently a Senior Communications Advisor with the Ontario Institute for Regenerative Medicine. With a background in fine art, communications and journalism, Lisa continues to moonlight as a writer, photographer and editor, contributing to a range of Canadian and US-based publications. In 2014, she was invited alumni-in-residence for the acclaimed Science Communications program at the Banff Centre. Follow her on Twitter and Medium @WillemseLA

The opinions reflected in this post are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Canadian Blood Services nor do they reflect the views of Health Canada or any other funding agency.

Related blog posts

A research, education. and discovery blog Did you know that we do research? Quite a lot of it, in fact. Last year, our research teams, working in our labs across Canada, published 250+ scientific papers in peer-reviewed journals and presented 200+ posters or talks at major national and international...

" The ever-present need for innovative ways to combat dengue and other emerging viruses and pathogens has never been clearer."