Innovation150 series: As Canada celebrates 150 years we look back on Canadian innovations in transfusion medicine over the years. A series of posts over the next few weeks feature remarkable Canadian progress -- past, present and future. #Innovation150.

Modern blood banking and transfusion medicine owe a great deal to Canadian wartime pioneers in battlefield medicine. For example, Dr. Lawrence Bruce Robertson’s insistence on whole blood for treatment of battlefield shock and hemorrhage established its medical importance in transfusion. This happened just as research on sodium citrate as an anticoagulant and buffers for red blood cell storage made advance collection from donors a more feasible option. However, it took another war before a civilian blood banking and transfusion service got started in Canada. Again, Canadian residents can thank pioneering wartime doctors for making it possible.

Dr. Norman Bethune and the Canadian Blood Transfusion Unit

Mobile blood banking for transfusion medicine featured in front-line medicine during the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939), when Canadian doctor Norman Bethune volunteered for action alongside the International Brigade. After receiving his medical degree in 1916, Bethune completed internships and worked in private practice before studying under Dr. Edward Archibald in thoracic surgery in Montreal.

This was the same Archibald who pioneered sodium citrate as an anticoagulant during World War I battlefield transfusion treatment. When Bethune didn’t find an opportunity to offer his surgical services in Spain, it was this experience in transfusion medicine from surgical practice that proved most valuable. Knowing that soldiers with battlefield injuries frequently benefit from treatment with whole blood, he saw an opportunity to support patients on the front line, using his transfusion experience to outfit a van as a mobile blood service.

![Canadian Blood Transfusion Unit which operated during the Spanish Civil War. Dr. Norman Bethune is at the right. ca. 1936 - 1938 Canadian Blood Transfusion Unit which operated during the Spanish Civil War. Dr. Norman Bethune is at the right. ca. 1936 - 1938 / Spain Source: [http://www.collectionscanada.ca/ Library and Archives Canada] Copyright: Expired](/sites/default/files/styles/max_325x325/public/Norman_Bethune_transfusion_unit_1936.png.jpeg?itok=EMjIlX_a)

Dr. Norman Bethune (right) Canadian Blood Transfusion Unit which operated during the Spanish Civil War circa 1936-1938, Spain. Source: Library and Archives Canada Copyright: Expired.

Mobile Blood Banking

Bethune’s Canadian Blood Transfusion Unit operated out of Madrid and covered a wider area than the other mobile services operating at the time. It tested out the refrigerated storage developed by a Spanish mobile transfusion team under Dr. Frederic Durán-Jordà, a hematologist working out of Barcelona.

The Canadian Blood Transfusion Unit brought blood donated by civilians to front-line hospitals and organized rapid transport of type O blood, the universal donor. Bethune claimed in one interview that the unit had collected and processed more than 340 litres of blood over one year of service.

Although Bethune left Spain after a year, his work with the mobile transfusion service is seen as an important contribution to modern Canadian transfusion service.

- Bethune organized a civilian volunteer base for donations and rapid transport for type O blood to the front line.

Dr. Charles Best and blood products for military hospitals

Dr. Charles Best, possibly most famous for his association with Frederick Banting’s Nobel Prize–winning work on insulin, pioneered methods for blood product storage that made them easier to ship overseas to the battle areas in World War II. His research and development of dried plasma products and validation of serum instead of whole blood for treating shock increased the versatility of blood banking and transfusion services for emergency medicine. This work, in conjunction with the Canadian Red Cross and government support, led to the establishment of the country’s first national blood banking and transfusion service.

- Best is most famous for his association with the Nobel Prize in Medicine for the isolation of insulin. Best was the student helper Banting acquired to help with his lab work one summer.

Blood products for easy transport and for transfusion safety

When Banting won the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1923, he shared the prize money with his student , Charles Best. With this money and his newly acquired medical fame, Best joined colleagues at Connaught Laboratories, redirecting his pre-War research program to explore the limitations encountered with transfusion medicine during World War I and investigate novel ways to store blood products.

Problems with whole-blood coagulation and storage meant that blood stocks were not plentiful, and soldiers often acted as “walking blood donors.” Furthermore, transfusion reactions due to incorrect blood-group matches still limited the service. Although further work had taken place to clarify blood typing in the years since World War I, incompatible transfusions still caused deaths. The crude matching tests that mixed donor and patient blood to check for clumping before each transfusion weren’t always easy to read.

Concentrating on these challenges, Best and his team worked on methods for preserving blood in long-term storage, and for cell-free alternatives to whole blood that might reduce transfusion reactions.

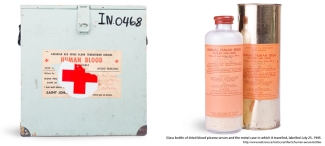

Best and his colleagues developed methods of separating whole blood, removing the fluid components — plasma (the liquid left after cells are removed) and serum (plasma without clotting substance, fibrin) — from cells. Once dried, the blood products could be shipped in a more stable form with a greater shelf life. Once the product arrived at the battlefront, clinicians simply reconstituted it by adding sterile distilled water before transfusing it into patients.

Human serum bottles and travel case, http://www.redcross.ca/history/artifacts/human-serum-bottles

The Serum Project

In addition to improving storage methods for blood products, Best also initiated the Serum Project. He demonstrated that administering serum rapidly improves the low blood pressure commonly encountered during shock. His experiments showed that following infusion, serum proteins remained in circulation long after colloids such as sodium chloride escaped. These proteins generated an osmotic pressure that helped build circulating volume to increase blood pressure. With this success, Best then optimized serum production and concentration methods, along with new drying techniques, so that the product could be shipped safely.

Canada’s civilian blood banking service

Best was also concerned with how this new medical advancement would be supported within Canada. He promoted voluntary donation, giving economic justification for this as a way to expand transfusion services to all Canadians, rich and poor. With this in mind, Best favoured the Canadian Red Cross for setting up national donation and blood banking, with initial efforts going to support the Armed Forces overseas. This set-up was successful, with massive public support for the war effort: “approximately 890,000 blood donations were collected from Canadians for military hospitals during the last year of the war” from a Canadian population at the time of only just over 11 million.

As a direct consequence of Best’s work in championing voluntary donation and alternative blood products, a civilian blood transfusion scheme and donor program began shortly after the war ended in 1945.

Written by Amanda Maxwell, with grateful thanks to Dr. Jacalyn Duffin, Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, for additional insights and materials.

References

Kapp, R.W. (1995). Charles H. Best, the Canadian Red Cross Society, and Canada’s First National Blood Donation Program, Canadian Bulletin of Medical History, 12(1). http://dx.doi.org/10.3138/cbmh.12.1.27

Canadian Blood Services – Driving world-class innovation

Through discovery, development and applied research, Canadian Blood Services drives world-class innovation in blood transfusion, cellular therapy and transplantation—bringing clarity and insight to an increasingly complex healthcare future. Our dedicated research team and extended network of partners engage in exploratory and applied research to create new knowledge, inform and enhance best practices, contribute to the development of new services and technologies, and build capacity through training and collaboration. Find out more about our research impact.

The opinions reflected in this post are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Canadian Blood Services nor do they reflect the views of Health Canada or any other funding agency.

Related blog posts

Innovation150 series on the RED blog: As Canada celebrates 150 years we look back on Canadian innovations in transfusion medicine over the years. A series of posts over the next few weeks feature remarkable Canadian progress in transfusion medicine past, present and future. #Innovation150.

It's National Blood Donor Week and we're celebrating blood donors from across the country who make a lifesaving difference to patients in need. Each of us has the right blood type to give life: ABOAB. This acronym refers to four blood groups — A, B, AB, and O. Blood type is one way we are all...

![L. Bruce Robertson beside Canadian Red Cross truck, ca. [1914-1918] Copyright: Queen’s Printer for Ontario L. Bruce Robertson beside Canadian Red Cross truck, ca. [1914-1918] Copyright: Queen’s Printer for Ontario](/sites/default/files/styles/max_325x325/public/blog_images/teasers/Bruce_Robertson_beside_Canadian_Red.png.jpeg?itok=8iC6GnaS)